Companies Keep Buying Future Fusion Power That Definitely, For Sure, Absolutely Will Exist

Hello, welcome to my relaunched newsletter, read more about the deal here and please subscribe!

The Italian oil and gas giant Eni announced an agreement on Monday to buy electricity "worth more than $1 billion" from a power plant that has not been built but totally, definitely, no-question-about-it will be built on its stated schedule. That power plant would be Commonwealth Fusion's ARC project, located in Chesterfield County, Virginia.

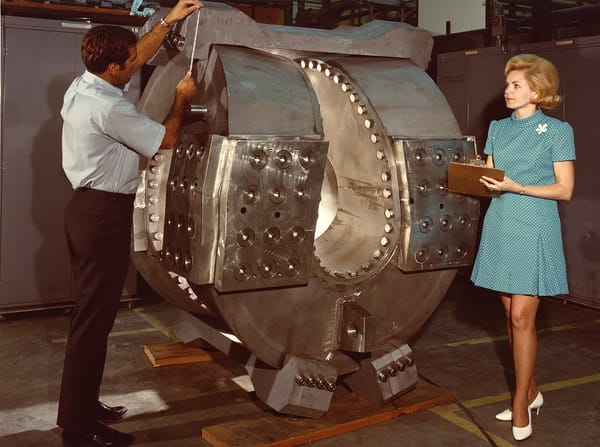

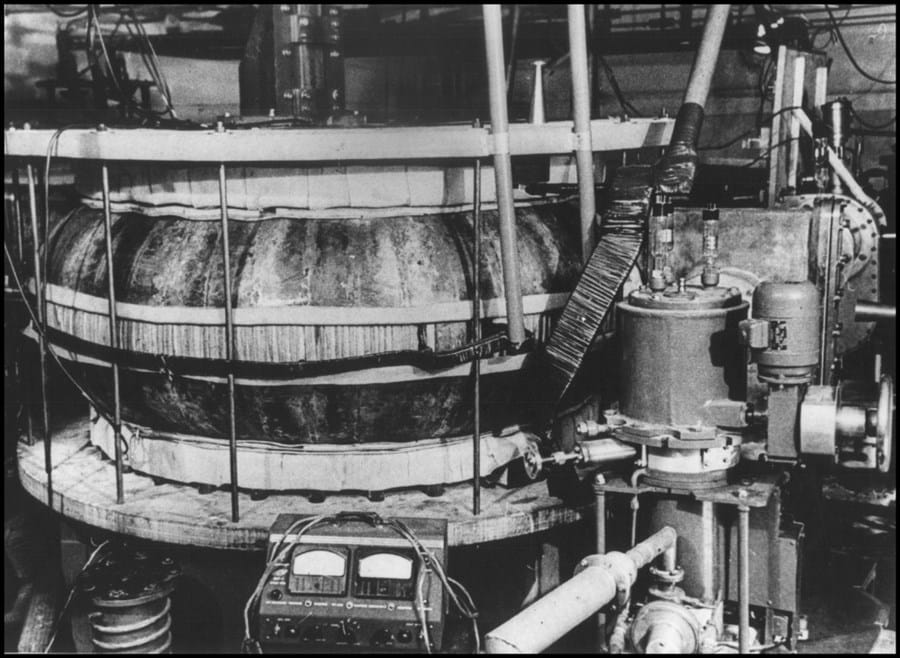

Well, theoretically located there. Construction isn't slated to start on the tokamak — essentially big donuts using incredibly powerful magnets to hold superhot plasma in place to allow fusion reactions to occur and generate energy — fusion reactor for another few years. In the meantime, the company has said its prototype reactor SPARC is around 65 percent finished; so, Eni is buying a billion dollars of power (the actual financial terms of this deal were not disclosed, the billion is apparently just an estimate of what the electricity would be worth) from a second-generation technology before the first generation has even been built, let alone demonstrated the more-power-out-than-in requirement to make fusion tech viable. Why they are buying it is also somewhat nebulous.

This sort of thing appears to be accelerating. Back in 2023, Microsoft became the first major company to purchase "electricity" from a fusion company, Helion Energy. Earlier this year, Google joined the party, agreeing to purchase 200 megawatts of power again from Commonwealth Fusion — though the industry has dozens of companies of varying sizes, the Massachusetts-based MIT spinoff has raised around $3 billion on its own, representing almost a third of all fusion investment to date.

Commonwealth has said its commercial reactor, now slated to sell power to Google and Eni, will connect to the grid in the early 2030s. Helion is even more bold: they announced that construction on their supposedly first-in-line reactor began at the end of July this year, at a site in Malaga, Washington. It is slated to deliver power starting in 2028. That is, at most, 39 months from now.

Fusion, of course, has been a few years away for something like 60 years. The modern fusion startup industry is, admittedly, closer than ever before, with various demonstrations out there (some of them at government facilities not actually designed to deliver usable power, however) certainly moving closer to actual positive power output. But that doesn't mean we should take these companies' word on their plants' imminence.

I have written about this before, but fusion companies love nothing more than to move a goalpost. In 2004, General Fusion, based in Canada, promised to demonstrate its plant by the end of 2006; that later shifted to 2010, then 2015, then they promised to "commercialize" fusion tech by the end of the 2010s. At its latest announcement in August of a closed funding round — $22 million, congrats — General Fusion says it will be "delivering fusion power to the grid by the mid-2030s."

Helion, the company currently building in Washington and ready to sell 50 megawatts of fusion power to Microsoft by 2028, previously said it would have a commercial plant operating within about five years. That was in 2014.

The optimism from within the industry is more or less ubiquitous — which makes sense for companies that exist in a sort of perpetual venture capital funding cycle. The Fusion Industry Association's annual survey of its members, out in July this year, showed that fully 40 of 45 responding companies think they will have a "commercially viable pilot plant" by 2035 (five companies said before 2030). Asked when they believe the first fusion power plant will deliver power to the grid, only seven respondents thought we'll have to wait until into the 2040s or beyond.

I have gotten mildly yelled at, in the past, for fusion skepticism. I would love to be wrong! Obviously! And it makes sense that no one has cracked this yet — fusion is hard, controlling hundred-million-degree stuff with magnets or lasers is as complicated a scientific and technological challenge as there is. As long as the money flowing to these companies isn't directly pulled from more immediate energy solutions like wind and solar — worth remembering, we are actually already really good at using the sun's fusion reactions to generate electricity, via that quaint technology, the solar photovoltaic panel — then I say keep going. Just stop calling it a climate change "solution" when it doesn't yet exist and we need to replace fossil fuels yesterday.

For the moment, though, congrats to Eni, the proud new owners of $1 billion of clean, 100-percent real, not-at-all-theoretical, fusion-generated electricity.