This Whole Thing Really Snuck Up On Us

Looking back, and ahead, on the anniversary of a White House warning.

"Through his worldwide industrial civilization, Man is unwittingly conducting a vast geophysical experiment."

So begins the conclusion to one little corner of a report — appendix Y4, specifically. It was part of a broad document from scientists and experts delivered to the White House titled "Restoring the Quality of Our Environment," which examined the sources and impacts of a wide array of forms of pollution. The appendix focused in, specifically, on "Atmospheric Carbon Dioxide."

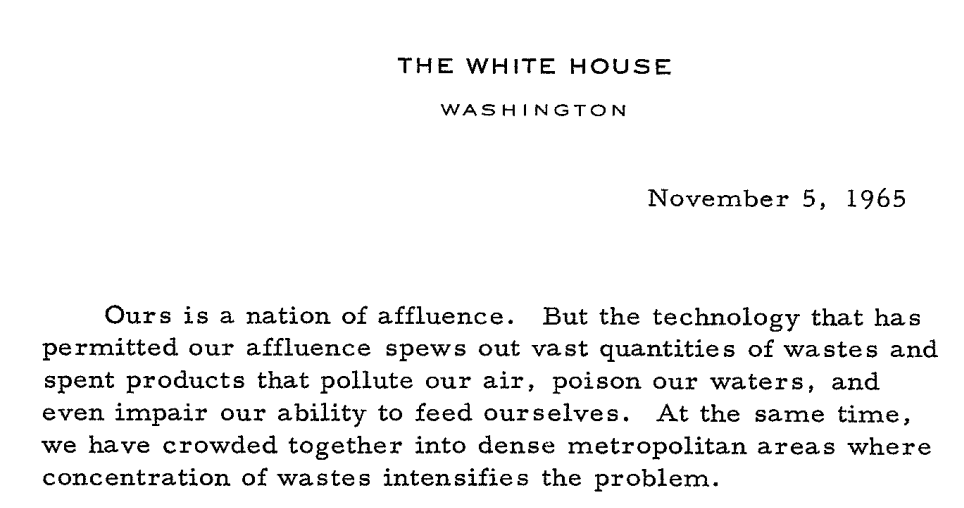

In releasing the entire document to the public, the president of the United States included an introductory letter. "Pollution now is one of the most pervasive problems of our society," he wrote. The rise in such filth sent skyward and into water supplies, he went on, "is so rapid that our present efforts in managing pollution are barely enough to stay even, surely not enough to make the improvements that are needed." And finally: "Because of its general interest, I am releasing the report for publication." The date on that letter was November 5, 1965.

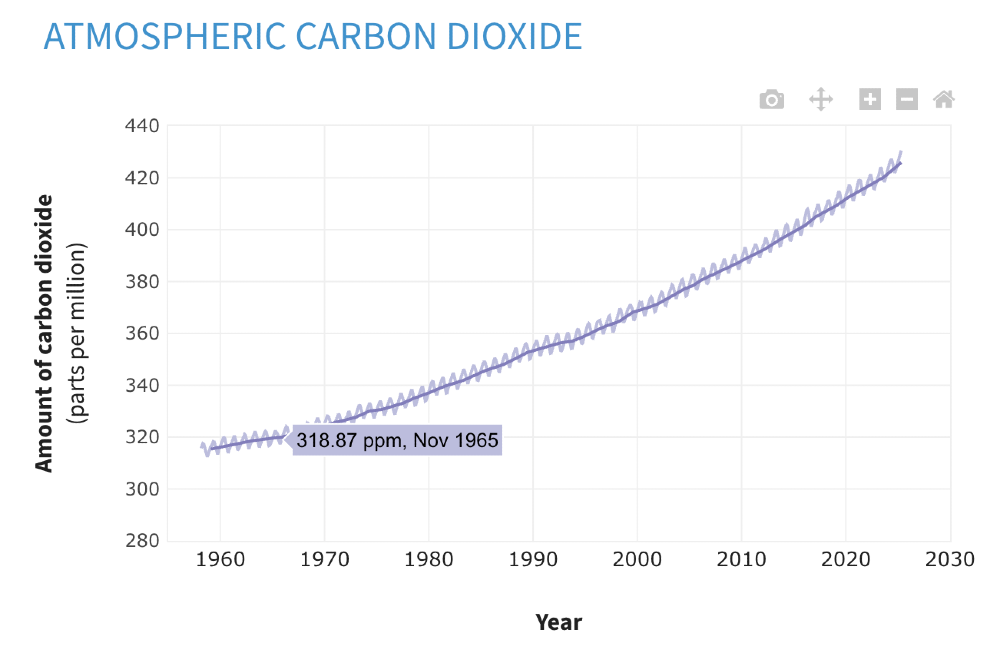

It has now been an astonishing 60 years, to the day, since the richest country on the planet issued its first high-level, governmental warning about the dangers of increasing greenhouse gas concentrations in the atmosphere. The authors made clear that the details were still hazy, in the sense that the precise response of the climate to specific amounts of increased CO2 at that point had a relatively wide range. Exactly how much warming was on its way was nebulous; that it was, in fact, on its way, was not.

They estimated that a 25-percent increase in atmospheric CO2 "compared to the amount present during the 19th century" could yield a temperature increase between 0.6° Celsius and 4.0° C (1.1° F to 7.2° F). They guessed that milestone would arrive around the turn of the century — they were wrong. In November 1965, the concentration of atmospheric CO2 had risen from that pre-industrial level of about 280 parts-per-million to 319 ppm; it crossed 350 ppm, that 25 percent threshold, in 1988. Today it sits at 425 ppm, more than 50 percent higher than before humans got busy burning things.

Though they emphasized the need for better modeling and measurement to nail town the temperature increase, the authors did write that even that 350 ppm mark would produce "measurable and perhaps marked changes in climate, and will almost certainly cause significant changes in the temperature and other properties of the stratosphere."

The report went on to describe some of the potential effects of this "unwitting" experiment, including the melting of ice caps and subsequent sea level rise, acidification of water sources, and more that has become familiar in the years since. And in the end, a technocratically worded but doom-tinged conclusion: "The climatic changes that may be produced by the increased CO2 content could be deleterious from the point of view of human beings."

The blame, throughout appendix Y4, was put squarely on its proper target: "We can conclude with fair assurance that at the present time, fossil fuels are the only source of CO2 being added to the ocean-atmosphere-biosphere system." It even offered estimates of the excess carbon that might be added in the future based on recoverable reserves of coal, oil, and gas — and we have found a lot more of the stuff since then. I think, more often than is healthy, about a line from yet another decades-old climate change report, from EPA authors in 1983: "[T]he shift away from fossil fuels perhaps could be instituted more gradually and therefore less expensively if energy policies were adopted now rather than several decades later."

Please consider a paid subscription to support work like this, or leave a tip

Funny story — the UN's climate conference, COP30, is set to open in a few days in Brazil; it took until just a couple of years ago before the world's countries could even deign to admit, in writing, that phasing out fossil fuels is probably a good idea. There is, finally, substantial progress happening on that front, American backslide notwithstanding; unfortunately, "several decades later" has come and gone.

The UN Environment Programme, in releasing its latest "emissions gap" report on Tuesday, finally admitted something scientists have been saying for a couple of years now: warming beyond 1.5° C, the ambitious target set forth in the Paris Agreement a decade ago, is now inevitable, "very likely within the next decade." The updated emissions pledges countries must submit — a requirement that only a third or so actually fulfilled as of the end of September — would still yield as much as 2.5° C of warming. Catastrophic.

The meeting in Brazil will be the thirtieth iteration of the multilateral climate negotiations process; the first took place in 1995, in Berlin. In other words, the world waited three full decades from that original warning reaching LBJ's desk to actually get together and try to do something about it; in the meantime, the evidence accumulated, more and more reports were issued, scientists testified before Congress, and oil companies engaged in years-long diabolical manipulation of the information environment to maintain their stranglehold on our energy systems. And then we spent two decades dithering until the Paris Agreement emerged from the multilateral process, and then we spent a decade failing to live up to its toothless requirements.

"Ours is a nation of affluence," wrote Johnson, at the start of his letter releasing the 1965 report. The technology that "permitted our affluence," he went on, was the culprit behind the increasing pollution problems. Though it took until his successor's term in the White House, the federal government did, in fact, take relatively substantive steps to address much of the pollution discussed in the report — only a few years later we got the EPA, important amendments to the Clean Air Act and passage of the Clean Water Act, and more. The rivers, you probably noticed, are no longer on fire. But the details in appendix Y4 did not have the same galvanizing effect as more pressing pollution problems, and the world, unfortunately, is.