When the Glaciers Go, They Won't Come Back

Shaving every tenth of a degree off whatever final thermometer number we end up at means a few more glaciers hanging on, diminished perhaps, but a glacier still, with room to grow.

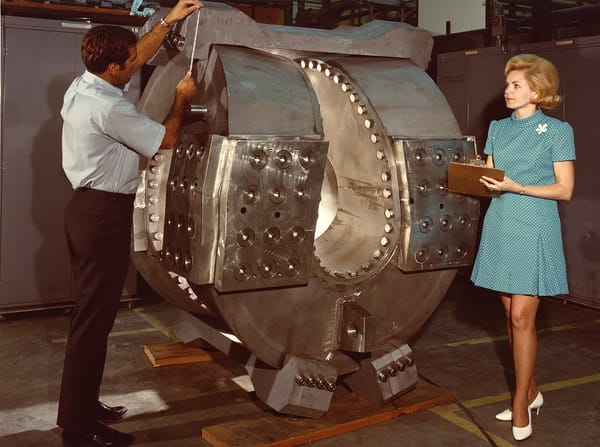

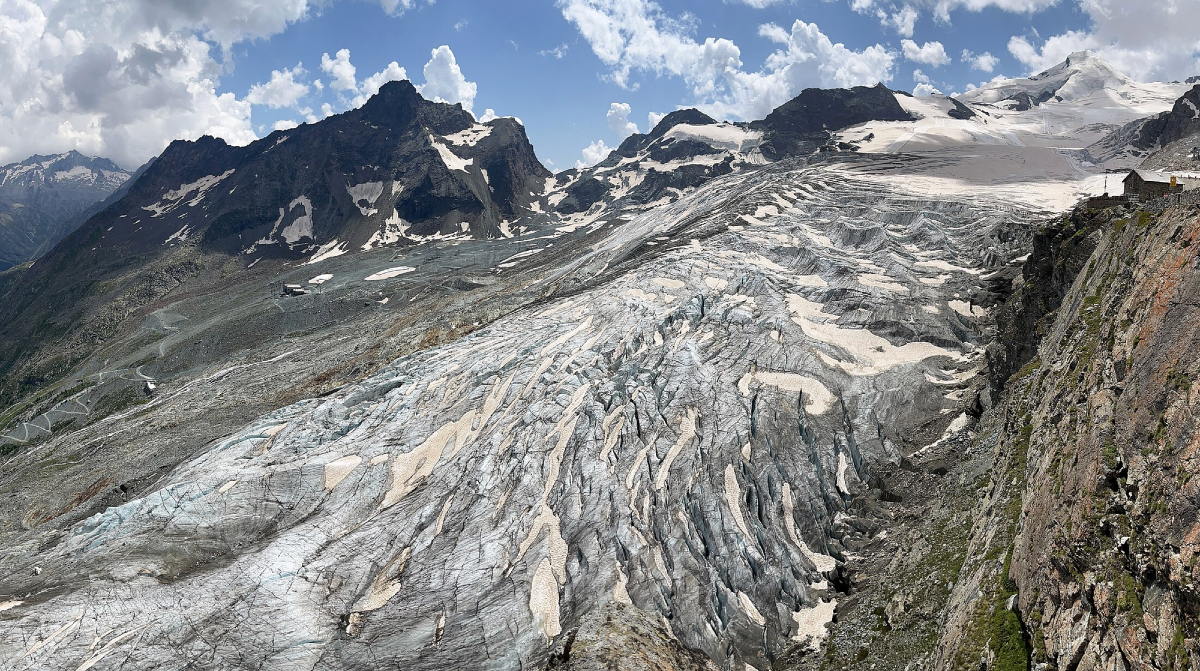

It takes a while to make a glacier. The result of years upon years of snowfall layered upon snowfall, compressed into ice that eventually becomes massive enough that its weight causes it to flow, slowly, across landscapes all over the planet that are left changed underneath and behind them. It is taking substantially less time for humans to kill them off.

In 1973, the Swiss Alps had over 2,700 individual glaciers; by 2016, that number was 1,400, and almost 30 percent of the glacial area was gone. That's not even today's real bad news.

Those numbers come from a study published last month in Annals of Glaciology, and as the authors point out, a whole lot more melting has gone on since 2016. In fact, a June 2025 study estimated Switzerland lost another 13 percent of all of its ice volume from 2021 to 2024 alone. Western Canada and the continental US, if you're curious, lost 12 percent in the same period.

Those looks back at vanished ice are grim, but today's real bad news, meanwhile, looks ahead at the remaining ice's future. In Nature Climate Change on Monday, researchers used three different glacier computer models to estimate a "peak" rate of loss, guessing at years when the disappearance of the meandering giants will top out. This depends on what the world does about climate change, of course — but if we stick to the current path, where existing policies and pledges cement the disastrous failure of the Paris Agreement and lock in something like 2.7 degrees Celsius of warming, we can expect only about 20 percent of existing glaciers around the world to remain by 2100. Four out of every five, gone.

That peak, under the current trajectory, will last decades — we will lose around 3,000 individual glaciers per year, every year, from somewhere around 2040 through 2060 or beyond. The pace only drops, of course, because there are so many fewer of them around to melt.

Glacial melt does not carry the weight of global catastrophe the way the melting of the Greenland and Antarctic ice sheets does. When those go (a centuries-long process, even in a worst-case scenario), they reshape the map of the world, rising sea levels by dozens or hundreds of feet. Mountain glaciers disappearing offer their own impacts, from reduced water supplies to potential for catastrophic local flooding to loss of revenue to people who live nearby.

"Every glacier is tied to a place, a story and people who feel its loss," said one of the researchers on the new study, ETH Zurich's Lander Van Tricht. "That’s why we work both to protect the glaciers that remain and to keep alive the memory of those that are gone."

And that's the thing — they won't come back. Not on meaningful time scales anyway. It takes too long for a glacier to grow, those layers upon layers of snow needing years to compact and compress and start to flow, and they won't do that anyway in a world that will still be warm, too warm, warm enough to make them vanish in the first place. But that new study pointed out the vast difference between 1.5 degrees C of warming — a ship that has sailed, perhaps, but instructive nonetheless — and about half the glaciers disappearing, and a hellish 4.0 degrees C and likely more than 90 percent gone. The gap between those pathways is large, and shaving every tenth of a degree off whatever final thermometer number we end up at means a few more glaciers hanging on, diminished perhaps, but a glacier still, with room to grow.